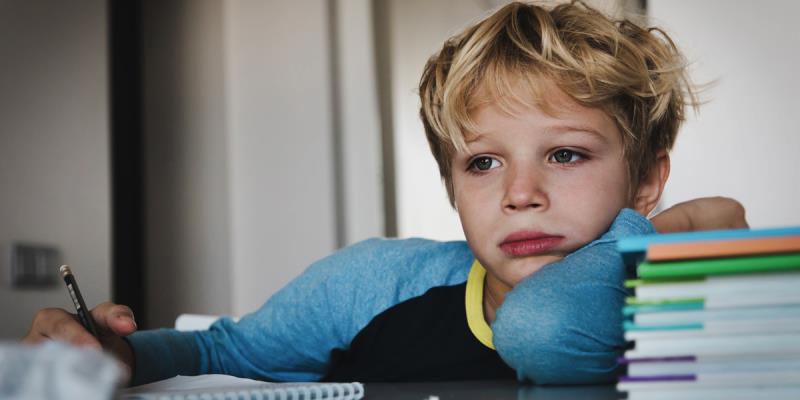

Coping with a child's mental health at home

Published on Tue Sep 28 2021 in Family

Parents may often wish for a parenting manual, but never more so than when their child is affected by a mental illness. With one in four Kiwi kids experiencing a mental health issue before the age of 181, many parents will need to deal with this issue affecting their family.

In contrast to when today’s parents were young, there has been significant progress in the recognition and awareness of mental health issues that affect young people. This means that diagnosis and treatments are becoming increasingly accessible. In addition, the stigma that previously surrounded mental illness has diminished over time, making it easier to reach out for help.

Signs of mental health concern

It’s important to know the signs which may indicate that someone is struggling with their mental health. The following symptoms are some signs that your child or teen may need help2. One or two of the below symptoms may just be part of growing up, however if they have several of them over the course of a few months, it could be a sign of depression:

- Feeling stressed or anxious

- Feeling depressed or unhappy that doesn’t go away

- Lacking concentration and interest in school and usual activities

- Emotional outbursts such as anger and irritability

- Sleep problems

- Weight or appetite changes

- Being quiet or withdrawn at home and socially

- Being forgetful

- Experiencing unexplained physical complaints

These signs alone do not necessarily mean that they have a mental illness, as many can be symptoms of other issues such as puberty, lifestyle changes or other health issues. However, if you notice any of these signs and they are unexplained or ongoing, it is a good cue to start a conversation about mental health and perhaps consult your family doctor.

How to get help

Symptoms arising in their own children may be the first time some parents have had to deal with mental illness, and it can be confronting. Many parents may not know what to do or how to deal with the situation.

If your child is presenting with any hint of suicidal thoughts, or psychosis this should be treated as an emergency, the same way you would a heart attack or a stroke. Contact emergency services or a mental health crisis team without delay and stay with your child until help is available.

For less urgent concerns about mental health issues, a great place to start is your family doctor who can diagnose an illness or refer your child to a psychiatrist for more complex diagnoses. Depending on the type and severity of the illness, treatment may include a mix of hospitalisation, medication and therapies.

Feelings around diagnosis

It is common for diagnosis of a mental illness in a child to bring about a myriad of reactions and emotions for a parent, including:

- Embarrassment or shame – despite the level of occurrence of mental health issue in children, parents can still experience and/or perceive societal stigma around this issue.

- Fear – of what the future of the illness holds for their child.

- Confusion or disbelief – some parents may not understand why this is happening to their family, especially if there is no family history of mental illness.

- Guilt – parents may blame themselves and feel that something they did caused or contributed towards the illness.

- Relief – for some parents, diagnosis is a relief to finally have a reason for what their child has been experiencing.

- Helplessness – parents may not feel equipped to support their child through an illness or cope with the challenges mental illness brings to the family.

Whilst the above are normal reactions to the situation, they should not be long lasting. If you find yourself stuck in any of these emotions, reach out for help through your family doctor, therapist or councillor who can help you work through these feelings.

How to support family members struggling with their mental health.

Sometimes it can be hard to know how to help a loved one with their mental illness. The Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand suggests using the following strategies3:

- Learn about the disorder, its treatment, and what you can do to assist recovery.

- Understand the symptoms for what they are. Try not to take things personally or see the person as being “difficult”.

- Encourage the person to continue getting support, and to avoid alcohol and drug abuse.

- Try not to focus on blame or feeling responsible for contributing or causing factors in your loved one’s problem. Guilt, anger and other similar feelings can be common and make it harder to recognise your positive contributions to your loved one’s wellbeing, and harder for you to be that support.

- Get support to work through how you feel about what is happening.

- Help the person to recognise stress and find ways of coping. This may include helping to solve problems that worry them.

- Encourage the person to be more physically active, but without pushing or criticising them, as this may make things worse. Accepting the person as they are and having realistic expectations for them is very important.

- Find ways of getting time out for yourself and to feel okay about this. Caring for a family or whānau member experiencing a mental illness can be stressful. It’s important to maintain your own wellbeing.

Caring for the carer

When caring for family members with mental illness, burnout is common, so just like on an aeroplane it is important to put your own mask on first. Parents need to practice self-care, not only to prevent carer burnout, but also to demonstrate self-care to their child. Taking care of oneself is vital for sufferers of mental illness and their carers alike.

It is important to recognise the symptoms that caring for your child may be taking a toll on your own mental health. Some typical signs that you may need to seek help for your own mental health are4:

- Increased sense of mental fatigue, lack of concentration or mental fog.

- Feeling as though life stressors are overwhelming and unmanageable.

- Experiencing an overwhelming sense of guilt.

- Feeling hopeless and alone.

- Withdrawing oneself from social activities or talking about problems with family and friends due to shame or embarrassment for fear of being ridiculed, socially outcast, or judged negatively for causing their child’s problem/ being perceived as a ‘bad’ parent.

- Experiencing overwhelming sense of fear and anxiety about your child’s problem that it impairs concentration and ability to engage in other tasks.

- Decreased motivation to engage in activities that were once enjoyable.

Living with mental illness

Whilst some mental illnesses may be short lived, relapses later in life are common so time invested in learning coping strategies now is worthwhile. It is important to remember that even though mental illness can be scary for all those involved, it is exactly that, an illness, one that in most cases can be treated to help your loved one to return to their best self.

-

About Author: Momentum Life is a leading provider of Life insurance and Funeral insurance in New Zealand.

1. How to support a child or teenager with depression | Health Navigator

2. Nine signs of mental health issues | healthdirect

3. Looking after yourself & your family | Mental Health Foundation

4. Parenting a Child with Mental Illness or Disability: Anxiety House

The content provided in this article is for information purposes only. The information is of a general nature and does not constitute financial advice or other professional advice. To the extent that any of the content constitutes financial advice, it is limited to Momentum Life products only and does not consider your specific financial needs or goals. You should consider whether the information is appropriate for you and seek independent professional advice, if required.

All product information is correct at the time this article was published. For current product information, please visit the Momentum Life website.